1955: 11-Plus failure takes me to school in Guildford

- Brian Simmons

- Nov 27, 2020

- 20 min read

Updated: Nov 28, 2020

September 1955 - I start at St Peters RC Grammar School for boys in Merrow

(I tried hard to find an image of the old St Peters badge from the time I was there without success. If anyone has one I would be most grateful for an image - colour if possible)

.......................................ooOoo..............................................

My final year at St Peters Leatherhead was really geared up to preparation for the Eleven Plus examination that in those days marked the first major educational milestone in our young lives and in which success or failure determined the standard of secondary education we would receive.

The choice, particularly for us Catholics around Ashtead was relatively stark. If you passed the exam, no problem. You got to go to Wimbledon College and be taught by the Jesuit Fathers or to The John Fisher School at Purley. In either case some travel was involved.

Both of these were fee paying private grammar schools and were seen by Mum and her Catholic friends as the ‘be and end all’ of secondary education in the area; and of equal importance, passing the Eleven Plus meant you could go there without paying.

On the other hand if you failed the exam, well to be honest, in our house it just wasn’t an option that was discussed. This was because it meant that you finished up at the local secondary modern which in Mum's view was a disaster.

Now, after all this build up, you’re probably ahead of me. Yes, I failed the bloody thing. I was actually not very well on the day being in the aftermath of a dose of ‘flu which didn’t help. Well, that's always been my story. Whatever the reason, being off colour, not studying hard enough or simply not being bright enough, the result in-doors was terrible. It was as though the world had come to an end.

Dad wasn’t so fazed by the situation but Mum was really disappointed and there were hours of discussion over what should be done. In the event, and I’m eternally grateful to them both for this, they decided that they would pay for me to go, not to the Jesuits, but to St Peter’s at Guildford. This was certainly not in the same league as Wimbledon College or The John Fisher School but it was a private Catholic grammar school that had a good reputation, even if a bit second division.

The Second St Peter's

If my start at St Peter’s in Leatherhead had been troubled, Merrow was quite the opposite and I loved it from the outset. Around the end of July 1955 before term started in the September, we had been invited to an open day during the summer holidays when all the new boys and their families were shown around the school and introduced to the masters.

We were treated like royalty and conducted around the school by a senior prefect, smart in his white shirt, red tie, and red blazer with the crossed keys badge of St Peter on the breast pocket. I was so impressed by the uniform.

“I’m sure you’ll like it here Brian” he said, and turning to my parents, “Please follow me.”

To be fair, I imagine that we were only taken to the showpiece areas that included the main house, the chapel and the science building and the refectory where tea and cakes were laid on because as time went on I was to discover that not every corner of the school was so pristine.

Apart from the impressive Victorian grandeur of the old house, the high point for me was the science block. It was divided into three laboratories where, to my young eye, the long mahogany workbenches seemed to stretch into the far distance. Sinks with brass taps and curved spouts, Bunsen burners and tripods, glass jars of coloured chemicals and all manner of mysterious and exciting apparatus had me instantly hooked. Strange thing really, I didn’t know a test tube from a spatula but I was in heaven. It felt like a sort of homecoming.

The chemistry lab was the domain of father John McSheehy, a giant of a man who I got on with immediately. “Hello young man.” he said with a smile and a voice that was gentler than his size suggested. “Are you interested in chemistry?” “Oh yes.” I said without a clue what chemistry actually was.

Sadly this is not an image of the actual lab at the time I was there but one I found online that is similar enough to give an idea.

Father Mac was also Master of Discipline. Yes the cane was alive and well at Merrow and given Father Mac’s bulk I’m glad that one way or another over the following years I managed to avoid him having to swing it in my direction. Not that I was such a goody-two-shoes. I was just lucky.

The physics master was Father Peter Boulding who I also took to and who, although I had no reason to believe it then, would continue to be my friend long after my time at St Peters.

And so it was that in September 1955 I settled into my five-year stint at St Peter’s Private Grammar School for boys in Guildford. They were to be mainly happy if relatively undistinguished years.

The school was situated at Merrow on the outskirts of Guildford so travelling to school from Ashtead involved a 12-mile journey on the 408 bus and I remember it cost 11½d (just under 5p) for the 45-minute trip.

It was one of the green double-deckers run by London Country and we always tried to go upstairs if there was space. You could see so much more from up there and it could get a quite exciting if the driver was behind schedule and had to put his foot down a bit because the top deck used to sway alarmingly especially around the bends at Clandon. I recall we were quite disappointed when the road was straightened and the bends lost their thrill.

Founded in 1947 the school had been developed around a Victorian mansion set in extensive grounds although the majority of the estate had been cleared to create playing fields. However in front of the main house there was (and still is) a stand of magnificently tall American Redwoods whose spongy bark used to fascinate us in the way you could punch it hard without injury.

The Headmaster was Father Wake and a number of the teachers were priests while the remainder were lay teachers – male of course. Apart from the kitchen staff and a couple of cleaners, the only female on site was Matron.

She was a strong but quite kindly woman of significant proportions who stood no nonsense from anyone up to and including the headmaster. If you were really poorly or seriously hurt she was as kind and gentle as Mother Teresa but malingerers got very short shrift.

The brick built refectory and kitchen adjoined the main house, beside which the large tarmac play area extended across to one of the sports fields.

A number of supposedly temporary buildings were occupied by the gymnasium, a chapel, science block and three classroom blocks whilst the old coach house was utilised as changing room, showers and toilets on the ground floor with the sixth form common room above. Another temporary building provided an assembly hall and also doubled as a music room.

The ‘temporary’ buildings were still in use when my own kids went there more than thirty years later in the 1980’s. They were timber framed and clad externally with white painted corrugated iron sheets and inside with a soft fibre insulation board painted in magnolia.

The roofs were open to the rafters and although lined, the corrugated asbestos sheets outside reverberated so loudly in heavy rain that it was almost impossible to hear anything.

Fairly ineffectual heating was provided by gas heaters that used to hang from the roof and had to be turned on and off by using a hooked stick to pull on a chain. I remember how their first use in the autumn terms always gave rise to a characteristic burning smell as six months of dust and dead insects quickly went up in smoke.

The chapel which was of the same construction had endured extremely well but the classrooms were showing their age. Eight years of fairly rough treatment by teenage boys had left their mark in the way of general wear and tear but the soft board lining had fared the worst. Years of wall charts and attack by innumerable drawing pins plus the odd bit of deliberate vandalism had caused the panels to disintegrate in places into irregularly shaped holes revealing the internal construction timbers. As a result when parents evenings came around ever-larger wall charts had to be found and pinned up in an attempt to conceal the state of affairs.

There were also a couple of tennis courts in the grounds and a former gardener’s store had been put to good use as the Tuck Shop. This used to open for twenty minutes every day after lunch and here we filled our pockets with four-a-penny Blackjacks, Sherbet Lemons, Flying Saucers, Refreshers, Fruit Gums and such like.

Beside the Tuck Shop could be seen the remains of the original enclosed kitchen garden, and nearby, against an old red brick wall, a fine if somewhat run down example of a Victorian lean-to greenhouse was pressed into service as the art-room.

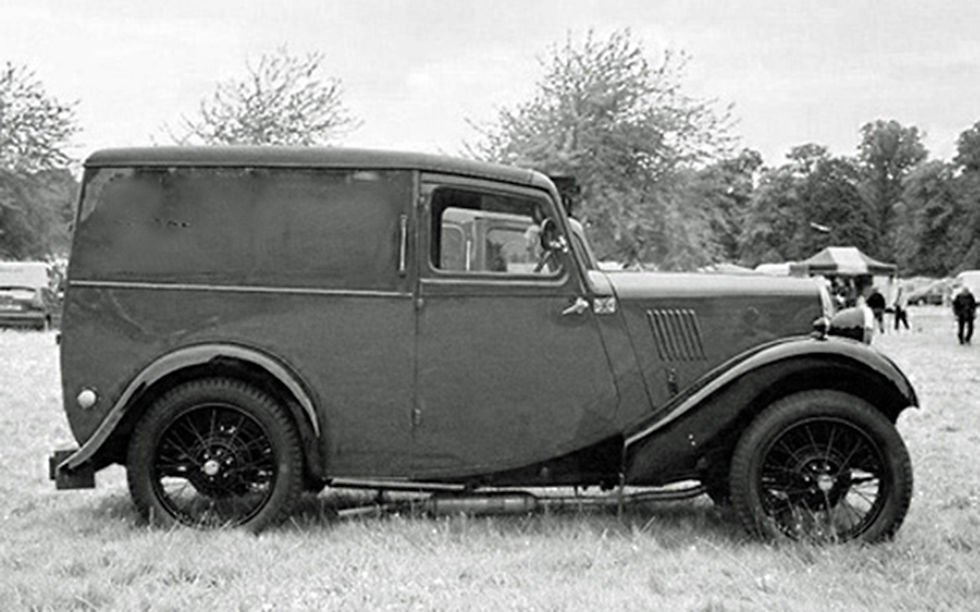

Along the other walls, even more dilapidated and overgrown, timber and brick stores housed a miscellany of ancient garden paraphernalia, broken pots, tools, cloches and most interestingly to my young eyes an old green Morris van.

Not surprisingly, I began my time at St Peter’s in the First Form and our form master, Father Stewart (I believe), was a pleasant enough man but presumably unremarkable as I can only just put a face to him with the help of an old photograph and if I’m honest couldn’t swear to his name.

Unlike primary school where class teachers seemed able to teach most subjects except music and PE, in this new environment form masters only took us for religious instruction and whatever other subjects happened to be their speciality. Consequently we had to get used to a procession of different teachers coming to the classrooms depending on what the next subject was on the timetable.

Every month a different class member was nominated as Form Captain who was supposedly responsible for keeping some sort of order in the absence of masters and there was also a door monitor whose job it was to be at the door and shout “Class!” to call us to our feet on the arrival of the next teacher.

Naturally some of these masters made more impression than others and for a variety of reasons. Some were notably bad teachers either by virtue of the fact that they could bore for England, had an inadequate grasp of their subjects or simply lacked the charisma or presence to inspire or exert any control. And believe me twenty or so twelve year olds need some control. One who had no problem whatever in the control department was a Father John Price.

A Glaswegian Scot, he was hard and if the mood took him could be a bully. He taught French and Latin and had this notorious penchant for tweaking the ears of miscreants, lobbing the blackboard rubber at the inattentive with unnerving accuracy and twisting the short hairs on the back of your neck in an attempt to remind you how some verb should be conjugated. I can’t imagine why he thought that might aid memory.

He was also an absolute stickler for discipline and was feared by us all in the junior forms. Interestingly though, when I was in the fifth form we had him as our form master and he was totally different in that relationship. He certainly still had the same reputation among the lower forms so clearly nothing had changed there.

So perhaps he just related better to older boys or dare I say he thought that if he took the same tack with a bunch of older and physically more mature boys he just might not get away with it. Who knows, but he was certainly very different and we became very fond of him, in what for many was to be our last year.

Another master who I will always remember was Henry McCann. He was short, very round and sort of bowled rather than walked along. As he always wore his mortar-board hat and academic gown that hid his legs he appeared to be on wheels. He had a plump ruddy face with wispy hair and gold-rimmed spectacles and looking back on it, was a bit too ‘touchy – feely’, which, with his somewhat lascivious smile that would raise alarm bells nowadays.

Henry McCann was however a very gifted teacher. He taught us English, Latin, French and Music and was extremely clever in the way he managed to interest a bunch of teenage boys in what on the face of it for many are dreary subjects. Basically he bribed us. It was the carrot and stick approach without the stick, but the carrot was that if we worked he would read to us on Friday.

He had the most wonderful ability to read aloud and to totally hold in thrall a group of youngsters who in any other circumstances would have had their minds on chatting, looking out of the windows; anywhere but on the English or Latin under discussion.

So from Monday to Thursday we would give him what he asked so that on Friday afternoons he would read. He always came and sat in the middle of the class and we all gathered around. He held us totally spellbound with the doings of Holmes and Watson as they sought to overcome the dastardly Moriarty or Fu- Manchu; and we quaked as he gave us Poe’s Pit and the Pendulum or Dickens’ Tale of Two Cities punctuated with the sickening thud of the guillotine.

Music was Henry’s main love though and here too he had a trick or two up his sleeve. Singing classes were not exactly high in the popularity listings for us boys but once again the carrot approach worked. I can remember standing around the piano in the music room at St Peters while he played to us. He was unbelievably good and could sit there without a sheet of music and simply play.

My two favourites were Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No1 and the Chopin Polonaise in A and I have no doubt that it was Henry McCann who first awakened my appreciation of good music and that at the age of about 14. We were so blown away and infected by the music that when it came to Strawberry Fair and the other Olde English songs we just sang our little hearts out for him.

My class with Father Ryan in front of the chapel. I am rear right

Another master was ‘Old Hairy” or to be more polite Father Albert Ryan; a lovely, larger than life man who earned his nickname from the hairs that sprouted in profusion from his eyebrows, nose and ears. As his name suggests he was Irish with a loud booming voice and strong accent that carried from one class into another on the not infrequent occasions that he was inclined to raise his voice.

He had a small lightweight motorbike, something like a BSA Bantam or Francis Barnett 125 that he used to ride across the playground and which, with his bulk perched on top, cut a pretty humorous appearance.

There was the lovely occasion when by way of a joke a few of us pinched his bike and hid it behind the classroom block. Albert soon realised that the bike’s disappearance was a prank played by some of the kids but we could hardly contain ourselves as he stomped about the classroom complaining about it whilst the bike was just a few feet away.

After the class we returned it and he never was any the wiser.

I mentioned Father Boulding the physics master earlier. He also had a nickname, well, two in fact. One was ‘penguin’, due to his curious gait.

As he walked he used to swing his arms quite widely which resulted in a sort of waddling or penguin like appearance. He was also known and PeeWee from his initials P.W.

There was one hilarious incident that superbly confirmed the ‘penguin’ nickname. One day during a free period a couple of boys had been having a crafty cigarette in the classroom when someone spotted a master coming in our direction. Instantly stubbing out the fags they flicked them into one of the aforementioned holes in the softboard wall of the building and thought no more about it.

During the next period someone noticed that there was smoke coming out of the wall, which after a very short time increased to quite a significant amount. The master in charge got in a complete panic and ran out of the class shouting “Fire Fire” in response to which Peter Boulding came charging out of the science block with a fire extinguisher.

Following the instructions, he inverted the extinguisher to activate it not realising that he had the spout facing towards himself instead of at the fire.

The extinguisher went off spraying him with foam so that with his black clerical suit and a white front the penguin effect was complete.

By about the age of fourteen, in common with quite a few others I’d started to experiment with cigarettes and in order to buy them we had worked out a way of saving our bus fares by hitch-hiking home from school.

These days I’m sure this would give rise to a great deal of eyebrow raising because of the supposed risks etc. but I used to do it a couple of days a week on average although it was always in company with at least one friend.

Surprisingly we rarely had a problem getting lifts and quite often we’d manage to get a ride almost door to door. But if the lift were only part of the way then we’d just wait for the next bus and be thankful to have saved a few pence from the fare.

I was one of a little clique of three or four who usually went around together and this included the journeys to and from school. On the days we decided to ‘hitch’ we took a short cut from the school along an alley-way and it was here that we used to stop and do the ‘smoking thing’.

One or two others knew about this and I guess wanted to be part of this risky and therefore slightly exciting activity but we were not very keen to extending ‘membership’ of our little gang to others. One boy, Michael Watson had become very persistent about wanting to try the smoking and was becoming a bit of a pain so we decided to try to put him off.

Nicky Hunt, whose mother kept horses had an idea and he made up some cigarettes from dried horse manure and a couple of days later on the way home when Watson was again trying to edge his way into the illicit smoking group we struck. “Ok” said Nicky. “Try one of these, they’re Turkish”. Watson lit up and took a puff and started to choke.

“Christ” he said, “They’re horrible. Taste like shit.” We were falling about by now.

“That right.” said Nicky. “Exactly right. They’re horse shit.”

Poor old Watson went a few shades of green before he finally threw up but he didn’t bother our little group again. Kids can be so cruel.

I think I was in the fourth or fifth form that we got up to another hilarious stunt (hilarious that is in an immature teenage boy sort of way).

There used to be a coffee and burger bar near Tunsgate in Guildford called Boxers that we liked to visit sometimes after school. It is now the Positano Cafe-Bar. I was in there one day with a couple of mates who’s actual names I cannot now recall except that one was about a year older than me and we all thought he was really cool because he used to smoke Philip Morris cigarettes that no-one else had ever heard of. Because of this his nickname was ‘Smoker’.

We were drinking coffee at this table when ‘Smoker’ said “Watch this.”

On the table there was a bowl of sugar and a small jug of ketchup, so he excavated a little hollow in the sugar into which he tipped a liberal dollop of ketchup and then buried it in sugar. “Come on.” He said. “Let’s move.”

And we moved to another table to sit back and see what happened.

After a few minutes a chap came in with his girlfriend and sat down at the table and ordered two coffees. We were beside ourselves with anticipation as he was being really flash with this girl and making as though he was so sophisticated and knew how to treat her and so on.

The coffees arrived and he asked her if she wanted sugar. She said she did and then he dipped the spoon into the sugar bowl and before he realised what was happening had ladled a gloopy spoonful of sugar and red ketchup into her coffee. By now we were hysterical but before he could put two and two together we were out of the door and away, but of course the story doesn’t end there.

A few days later at assembly it was announced that a complaint had been received from Boxers about the behaviour of some St Peter’s boys and a brief description of the incident was given which caused huge hilarity all around.

The sting was that unless the culprits owned up by lunch time the whole school would be given detention for a week so after assembly we presented ourselves at the headmasters office all prepared to take the consequences. However before two of us knew what was happening ‘Smoker’ had said it was all his idea and took complete responsibility. (Those were the days when honour meant something even in school.)

We were then dismissed and told that we would be advised of any punishment in due course.

Presumably there was then some discussion between the school and the café owner because Smoker was told that his punishment was to go to the restaurant, admit responsibility, apologise and offer to pay for the wasted drinks and any other damage.

By most people’s standards this should have been a salutary experience and a good lesson learnt but Smoker had other ideas. That afternoon he strode in to the café, cool as you like and asked for the manager. Then apparently instead of making it clear he was the culprit, he acted as though he was a representative of the school and had come to apologise and make good any costs. Clearly he wasn’t recognised and the ploy worked a treat because apologies were accepted and he was treated to a free burger and coffee. Just goes to show that if you’ve got the neck you can get away with almost anything.

Sport was quite a big thing at St Peters and when I first went there we had to play rugby, which I absolutely hated, basically because I was terrified. I’d not had good experiences at primary school and being fairly slight of build and shy by nature was hardly a prime candidate for ‘prop forward’ or whatever it is rugby players are called. However it was obligatory and had to be endured so as a result I came to dread Wednesday afternoons.

Fortunately after the first year, for some reason I never knew, rugby was dropped in favour of soccer. But that was little better except that being marginally less of a contact sport I was able to avoid getting knocked about so much and used to just run up and down the pitch keeping as far away from the ball as possible.

The PE master would be shouting, “Go on Simmons. Get in amongst it.” and I’d say “Ok Sir.” and just keep running up and down. I was a real wimp on the sports field but then we are what we are I guess. I managed to exist in this way for three years when suddenly an escape route appeared.

It was announced that volunteers were being sought for the role of ‘laboratory assistant’ in the physics and chemistry departments. Duties would entail helping during break periods to set and clear up equipment in the laboratories and possibly from time to time having to miss games periods on Wednesdays.

I couldn’t believe my ears and lost no time in presenting myself for what I thought would be a selection process and being one of the chemistry ‘swots’ I was hopeful of being chosen. Well I needn’t have worried because there were no other takers and I became a ‘lab boy’.

It turned out to be a really excellent ploy for us. Especially useful as it quickly developed from being a couple of times a week and an occasional games period into a regular arrangement whereby more or less every break time and each Wednesday afternoon along with one other boy we disappeared to make the coffee for the two science masters Fr. Mac and Fr. Boulding.

This meant we also had coffee and biscuits as well as washing up a few test tubes and setting up experiments for following laboratory sessions. It probably worked well for the games master too because he didn’t have to worry about trying to persuade or order a couple of unwilling boys to try to play a game they clearly were not good at.

Over the next year of being ‘lab boys’ we got to know the two priests as both teachers and friends.

Out of the classroom environment they were much less formal and with their guard down so to speak the odd expletive would slip out.

I recall one day when Fr Mac managed to hit his thumb with a hammer. “Oh sod it!” he yelped and suddenly seemed much more in my world.

Away from school both priests were interested in trains and trams and were happy to share their interest with us. On several occasions out of school hours we went with them to visit transport sites of either current or historic interest.

Such a relationship between teachers and pupils would probably be frowned on today as inappropriate. I hope I’m not being naïve but I don’t believe there was anything of a dubious nature about it apart from perhaps an element of favouritism.

I believe that they honestly enjoyed sharing and encouraging our interest in a wider range of subjects. In addition, the relationship encouraged my interest in the sciences that eventually led me to examination successes.

It would be wrong to suggest that we were alone in these extra-curricular activities. I knew of other occasions when masters who had some special interest had taken groups of boys on visits to one place or another.

For example Peter Boulding took about six of us on a visit he had arranged through a parent to Lloyds of London and the Stock Exchange where we had the working of both organisations explained. And on another occasion he took three of us to the Transport Museum at Clapham.

I just think that these days such activities would have to be far more formal in arrangement and officially sanctioned whereas then there were not the same anxieties or suspicions.

I mentioned previously that there was an old Morris van parked in an outbuilding within the school grounds and as the other boy and I grew in confidence with the two science masters we decided to ask them if they would teach us to drive it. After initially dismissing the idea, when we continued to press them Fr. Mac eventually said, “Ok. If you can get it going I’ll think about it.”

Obviously we didn’t know much about how engines worked but we started by getting the flat tyres pumped up and I asked my Dad what to do about it.

“Well,” he said, “The battery will need charging but if you’re lucky it might not need much more than that.”

There was a charger in the physics lab so we hooked up the old battery that amazingly took and held a charge. Father Mac gave us a gallon of petrol and to everyone’s surprise after a few attempts the engine started.

It ran pretty roughly at first but by now the two priests had become more interested and after a bit of tinkering around between them the old van was running ‘as sweet as a nut’.

Good to his word Father Mac said he would give us some lessons after school. So, having advised our respective parents that we’d be a bit late home, the following week driving lessons around the field and playground began.

The van was a bit of a wreck really and with seats that were scarcely secured to the floor it was difficult to get into and maintain a position that allowed proper control of the pedals so as you might imagine progress was not exactly smooth. This, together with excessively worn steering and the almost complete absence of synchromesh on any of the three gears made our lessons something of an adventure.

The brakes worked OK even if they pulled a bit to one side. The problem was you never knew until you hit the pedal which way the pull would be so it was interesting to say the least. If this all sounds highly risky, it wasn’t really as within the confines of the grounds we never actually got over about 20 miles an hour so there was never any real danger but it was the most tremendous fun.

We had quite a few lessons that I guess must have been beneficial when I came to learn properly a couple of years later but unfortunately, despite all our efforts, the experience was to be quite short lived. The school tractor broke down and the grounds-man hi-jacked the old van to tow the gang mowers around the playing fields and sadly that was the end of our driving lessons.

I was no star student academically but I guess I held my own more or less ‘mid-field’ as you might say, apart from Chemistry and English, both of which I enjoyed and was quite good at. My bete-noir was maths, which I couldn’t understand and consequently hated.

Unfortunately as physics by this time had started to entail a fair amount of maths I had started to fall behind a bit there too.

In the fourth year it was the practice to enter students for a little-known public examination called The College of Preceptors; the idea being to give us some experience of public examination in preparation for the GCE ‘O’ levels that we would take the following year. I took eight or nine subjects and passed them all, three with distinction. The consequence was, for me at least, that I think it gave me a false sense of confidence.

As a result I didn’t work as hard as I should have done and so when it came to the ‘O’ levels the following year I failed pretty dismally, only passing in Chemistry, English Language and Literature.

Following this performance there was no question of my continuing to sixth form and ‘A’ levels. I felt very demoralised and as I guess my parents were pretty disappointed too it was made fairly clear that the time had come for me to call it a day and enter the world of work. So in July 1960 I walked out of St Peters and full time education for the last time.

As I said, my friendship with Peter Boulding was to endure beyond my school years and some twelve years after I first met him he officiated at my wedding and then baptised my son. Years later when I was struggling to make an unhappy marriage work I often sought his counsel so he was someone quite special to me for many years. However, that is jumping ahead somewhat.

For more memories of the years '44 to '64 about growing up in Surrey and much further

afield do have a look at my memoir Stepping Out from Ashtead published on Amazon in paperback and KIndle format.

Comments